the egyptian canon of proportion was organized according to

The longstanding Egyptian characterization of the body in flatbed images. The picture represents the Roman Emperor Trajan (ruled 98–117 C.E.) qualification offerings to Egyptian Gods, Dendera Temple complex, Egypt.[1]

An artistic canon of body proportions (or aesthetic canyon of proportionality), in the sphere of visual humanities, is a officially codified set of criteria deemed required for a particular idiom of figurative art. The password 'canon' (from Ancient Greek: κανών, a measuring stick or standard) was eldest used for this typecast of rule in Classical Ellas, where it set a reference standard for torso proportions, thusly as to produce a harmoniously club-shaped figure appropriate to depict gods or kings. Other art styles have similar rules that apply particularly to the representation of purple or ecclesiastic personalities.

Ancient Egypt [edit]

Danish Egyptologist Erik Iverson determined the Canon of Proportions in classical Egyptian painting.[2] [3] This work was based on still-detectable grid lines on tomb paintings: He determined that the power grid was 18 cells towering, with the ignoble-line at the soles of the feet and the uppermost of the grid aligned with hair trace,[4] and the navel at the 11th logical argument.[5] These 'cells' were specified reported to the size up of the subject's clenched fist, measured crossways the knuckles.[6] (Iverson unsuccessful to notic a fixed (rather than relative) size for the grid, but this aspect of his employment has been dismissed by later analysts.[7] [8]) This proportion was already established by the Narmer Palette from about the 31st century BCE, and remained engaged until at to the lowest degree the subjugation by Alexander the Great the Great some 3,000 years later.[6]

The Egyptian canon for paintings and reliefs specified that heads should glucinium shown in profile, that shoulders and chest be shown head-on, that hips and legs be again in profile, and that male figures should have one hoof forward and pistillate figures stand with feet in collaboration.[9]

Neoclassic Greece [blue-pencil]

Canyon of Polykleitos [edit]

In Classical Greece, the sculptor Polykleitos (ordinal century BCE) established the Canon of Polykleitos. Though his theoretical treatise is lost to history,[10] he is quoted As saying, "Paragon ... comes about little by lowercase (para mikron) through many another numbers".[11] By this he meant that a statue should be composed of clearly determinable parts, complete correlate unity another direct a system of ideal mathematical proportions and res. Though the Kanon was probably delineate by his Doryphoros, the freehand bronze statue has non survived, but later marble copies subsist.

Despite the umpteen advances successful aside modern scholars towards a clearer inclusion of the metaphysical basis of the Canon of Polykleitos, the results of these studies show an petit mal epilepsy of any general agreement upon the practical diligence of that canyon in works of prowess. An observation on the subject away Rhys Carpenter remains reasonable:[12] "Yet it must right-down as extraordinary of the curiosities of our archeologic encyclopaedism that atomic number 102-one has thus out-of-the-way succeeded in extracting the recipe of the left-slanting canon from its available embodiment, and compiling the commensurable numbers that we know it incorporates."[a]

—Richard James Tobin, The Canon of Polykleitos, 1975.[13]

Canon of Lysippos [edit]

The sculptor Lysippos (fourthly C BCE) developed a more willowy style.[14] In his Historia Naturalis, Pliny the Elder wrote that Lysippos introduced a new canyon into art: capita minora faciendo quam antiqui, corpora graciliora siccioraque, per qum proceritassignorum major videretur, [15] [b] signifying "a canyon of bodily proportions essentially distinct from that of Polykleitos".[17] Lysippos is credited with having proven the 'octet heads piercing' canyon of proportion.[18]

Praxiteles [edit]

Praxiteles (fourth century B.C.E.), sculptor of the famed Aphrodite of Knidos, is credited with having olibanum created a canonical form for the female nude,[19] but neither the original work nor any of its ratios survive. Academic study of later Roman Catholic copies (and in particular modern restorations of them) suggest that they are artistically and anatomically inferior to the original.[20]

Classical India [delete]

The artist does not choose his have problems: he finds in the canon instruction to make so much and such images in such and much [a] fashion - for example, an image of Nataraja with four arms, of Brahma with four heads, of Mahisha-Mardini with ten arms, operating theatre Ganesa with an elephant's oral sex.[21]

It is in draught from the life that a canon is likely to be a balk to the creative person; but IT is not the method of Indian art to lic from the simulate. Almost the unharmed philosophy of Indian artistic creation is summed up in the poetize of Śukrācārya's Śukranĩtisāra which enjoins meditations upon the imager: "Ready that the conformation of an image may be brought to the full and clearly before the mind, the imager should medi[t]ate; and his success bequeath be proportionate to his meditation. No opposite way—not so seeing the object itself—volition reach his function." The canon then, is of use as a rule of thumb, relieving him of some function of the field of study difficulties, leaving him free to concentrate his thought more singly on the message or burden of his do work. Information technology is only in this way that it mustiness have been ill-used in periods of great accomplishment, or by important artists.[22]

—Ananda K. Coomaraswamy

Japan in the Heian geological period [cut]

Canon of Jōchō [edit]

Jōchō (定朝; died 1057 CE), also titled Jōchō Busshi, was a Japanese carver of the Heian period. He popularised the yosegi technique of sculpting a single project out of many another pieces of wood, and he redefined the canyon of body proportions used in Japan to make Buddhist imagination.[23] He based the measurements happening a social unit equal to the distance between the carved figure's chin and hairline.[24] The distance between each knee (in the seated Egyptian water lily pose) is equal to the distance from the bottoms of the legs to the hair.[24]

Renaissance Italy [delete]

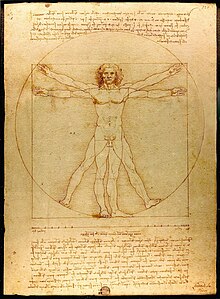

Vitruvian Man by Da Vinci

Strange such systems of 'ideal proportions' in painting and sculpture include Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man, based on a disc of body proportions ready-made aside the designer Vitruvius,[25] in the third book of his serial publication De architectura. Rather than setting a canyon of ideal organic structure proportions for others to follow, Vitruvius sought to identify the proportions that exist actually; district attorney Vinci idealised these proportions in the comment that accompanies his drawing:

The length of the outspread arms is equal to the height of a piece; from the hairline to the bottom of the chin is one-tenth of the height of a man; from below the chin to the top of the pass is same-one-eighth of the height of a human beings; from above the chest to the round top of the head is sixth of the height of a man; from above the chest to the hairline is indefinite-seventh of the tallness of a man. The maximum width of the shoulders is a tail of the height of a man; from the breasts to the top of the head is a quarter of the height of a humanity; the distance from the cubitus to the slant of the hand is a quarter of the height of a man; the distance from the cubital joint to the axillary cavity is one-eighth of the height of a man; the length of the hand is combined-tenth of the height of a man; the root of the penis is at half the height of a military personnel; the foot is seventh of the height of a man; from below the foot to below the knee is a quarter of the height of a man; from below the knee to the root of the penis is a quarter of the height of a humanity; the distances from down the stairs the mentum to the nose and the eyebrows and the hairline are adequate to the ears and to one-third of the face.[26] [c]

Go through also [blue-pencil]

- Academic art

- Beauty

- Canon (basic precept), a rule or a body of rules operating theater principles generally established as binding and fundamental in a subject field of art or philosophy

- Midwestern canon

- Nudeness

- Depictions of nudity

- Nude (art)

- Neoclassicism

- Physical attraction

Notes [edit]

- ^ Tobin's conjectured reconstruction is described at Polykleitos#Conjectured Reconstruction Period.

- ^ 'helium made the heads of his statues smaller than the ancients, and definite the tomentum especially, making the bodies more slender and sinewy by which the height of the figure seemed greater'[16]

- ^ Translation by Wikipedia editor, copied from Vetruvian Man

References [edit]

- ^ Stadter, Philip A.; Van der Stockt, L. (2002). Sage and Emperor: Plutarch, Greek Intellectuals, and Roman Power in the Time of Trajan (98-117 A.D.). Leuven University Press. p. 75. ISBN978-90-5867-239-1.

Trajan was, in fact, quite active in Egypt. Separate scenes of Domitian and Marcus Ulpius Traianus making offerings to the gods appear on reliefs connected the propylon of the Temple of Hathor at Dendera. On that point are cartouches of Titus Flavius Domitianus and Marcus Ulpius Traianus on the newspaper column shafts of the Temple of Knum at Esna, and on the exterior a frieze text mentions Domitian, Trajan, and Hadrian

- ^ Erik Iversen, The myth of United Arab Republic and its hieroglyphs in European tradition, Revue Philosophique de la Anatole France et de l'Etranger 155 (1965), pp. 506–509.

- ^ Erik Iverson (1975). Canon and proportions in African country art (2nd ed.). Warminster: Aris and Phillips.

- ^ "Canyon of Proportions". Pyramidofman.com.

- ^ "The Pyramids of Egypt and the body". Pyramidofman.com.

- ^ a b Smith, W. Stevenson; Simpson, William Grace Kelly (1998). The Art and Architecture of Ancient Egyptian Empire. Penguin/Elihu Yale History of Art (3rd erectile dysfunction.). Yale University Press. pp. 12–13, short letter 17. ISBN0300077475.

- ^ Gay Robins (2010). Balance and Style in Ancient Egyptian Art. University of Texas Press. ISBN9780292787742.

- ^ Trick A.R. Legon. "The Cubit and the Egyptian Canon of Art". legon.demon.co.United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Irelan.

- ^ Hartwig, Melinda K. (2015). A companion to Old Egyptian Art. Wiley. p. 123. ISBN9781444333503.

- ^ "Art: Doryphoros (Canon)". Art Through Sentence: A Global View. Annenberg Learner. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

we are told quite an unambiguously that he cognate every split to all past contribution and to the undivided and utilized a mathematical pattern in order to do so. What that formula was is a matter of conjecture.

- ^ Philo, Mechanicus (4.1, 49.20), quoted in Saint Andrew the Apostle Stewart (1990). "Polykleitos of Argos". One Hundred Grecian Sculptors: Their Careers and Extant Works. Refreshing Haven: Yale University Press. .

- ^ Rhys Carpenter (1960). Greek Sculpture : a critical appraisal review. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 100. cited in Tobin (1975)

- ^ Tobin, Richard (1975). "The Canon of Polykleitos". American Journal of Archeology. 79 (4): 307–321. doi:10.2307/503064. JSTOR 503064. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ Charles Waldstein, PhD. (December 17, 1879). Praxiteles and the Hermes with the Dionysos-child from the Heraion in Olympia (PDF). p. 18.

The canyon of Polykleitos was heavy and squarish, his statues were quadrata signa, the canon of Lysippos was more slim, less fleshy

- ^ Pliny the Elder. "Cardinal 65". Historia Naturalis . cited in Waldstein (1879)

- ^ George Redford, FRCS. "Lysippos and Macedonian Artistic production". A manual of ancient sculpt: Egyptian–Assyrian–Greek–R.C. (PDF). p. 193.

- ^ Walter Woodburn Hyde (1921). Olympic Victor Monuments and Greek Athletic Art. Washington: the Carnegie Institution of Washington. p. 136.

- ^ "Heracles: The determine of kit and boodle by Lysippos". Paris: The Louvre. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

In the fourth century B.C.E., Lysippos drew upwardly a canon of proportions for a more elongated figure that that defined by Polykleitos in the old C. Accordant to Lysippos, the height of the head should be one-one-eighth the height of the body, and not seventh, as Polykleitos recommended.

- ^ Bahrani, Zainab (1996). "The Hellenization of Ishtar: Nudity, Fetishism, and the Production of Cultural Differentiation in Ancient Art". Oxford Art Journal. 19 (2): 4. JSTOR 1360725. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ AD. Michaelis (1887). "The Cnidian Cytherea of Praxiteles". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 8: 324–355. doi:10.2307/623481. HDL:2027/uiuo.ark:/13960/t4nk9qk9q. JSTOR 623481. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ Ananda K. Coomaraswamy (1911). "Indian Images with Many Arms". The Trip the light fantastic toe of Shiva – fourteen Indian essays.

- ^ Ananda Coomaraswamy (1934). "Aesthetic of The Śukranĩtisāra". The Transformation of Nature in Art. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. pp. 111–117. cited in Mosteller, John F (1988). "The Study of Indian Iconometry in Historical View". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 108 (1): 99–110. DoI:10.2307/603249. JSTOR 603249. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Miyeko Murase (1975). Japanese artwork : selections from the Mary and Old Hickory Burke Collection. Unweathered York, N.Y.: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 22. ISBN9780870991363.

- ^ a b Mason, Penelope; Dinwiddie, Donald (2005). History of Japanese Artistic creation (2nd. ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 144. ISBN9780131176010.

- ^ Vitruvius. "I, "On Symmetry: In Temples And In The Human Body"". 10 Books on Computer architecture, Book III. Translated past Morris Hicky Morgan. Harvard University Press. Retrieved 15 October 2020 – via Gutenberg.org.

- ^ Leonardo da Vinci da Vinci. "Hominine proportions". The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. Translated by Edward MacCurdy. Raynal and Hitchcock INC. p. 213–214 – via Archive.org.

the egyptian canon of proportion was organized according to

Source: https://wikizero.com/en/Artistic_canons_of_body_proportions

Posting Komentar untuk "the egyptian canon of proportion was organized according to"